A week of Tai Chi in the vibrant seaside town of Falmouth in Cornwall

Monday 14th & Tuesday 15th 12:30 to 5pm

Wednesday 16th to Friday 18th April 2025 10 am to 4 pm

Golf Club, Above the Bay, Swanpool Rd, Falmouth TR11 5PR

T’ai Chi Saturday in the Church March 22nd

T’ai Chi Weapons Sunday in the Hall March 23rd

11 a.m to 4 p.m each day

The Hub Hazelwell

318 Vicarage Rd, Birmingham B14 7NH

Beginners are always welcome

Awaken Your Inner Strength: Weekend Tai Chi & Taoist Arts Course

Step into a space of calm and empowerment with our transformative Weekend Tai Chi & Taoist Arts Course. This immersive experience blends flowing Tai Chi movements, Taoist philosophy, and traditional weapons training to cultivate balance, strength, and inner harmony.

What You Will Experience:

🌿 Tai Chi Forms – Learn graceful, flowing movements that build energy, balance, and inner strength.

🌿 Qigong Exercises – Restore vitality and deepen your connection to breath and body.

🌿 Taoist Philosophy – Discover ancient wisdom for living with ease and natural flow.

⚔️ Traditional Weapons Training – Explore the art of Tai Chi sword and staff, enhancing focus, coordination, and energy flow.

🌿 Relaxation and Focus – Release tension and quiet the mind through mindful movement.

We welcome you to our Weekend of Taoist Arts

Saturday 25th January T’ai Chi from 11 a.m till 4 p.m

Sunday 26th January Kung Fu from 11 a.m till 4 p.m

Lunch is 1 p.m till 2 p.m. Tea is provided bring lunch .

Caludon Castle Sports Centre Axholme Road Wyken Coventry CV2 5BD

If you haven’t been to our courses before we offer tea at the break but bring lunch. Wear loose clothing and trainers or pumps. If you are already a member bring your grading cards and always write your notes as you may not remember everything you are taught on the course.

If you want to join the Association here is the link https://www.seahorsearts.co.uk/tcaa-student-membership-form/

This year our Summer Course will be hosted by the Penryn club in Falmouth, Cornwall. It is a picturesque location with beautiful beaches and also a deep harbour port, with a world-class Art college, two Universities, and a thriving student community.

Yes, believe it or not, slowness is a movement, in fact, it’s an institution.

At the heart of Taoist practice lies the principle of wu wei, or non-action, which is not about inaction but about taking action that is in harmony with the natural flow of the universe. Slow movement embodies this principle, teaching us to move with deliberation and awareness, aligning our actions with the Tao, the fundamental nature of the universe.

Chee Soo, a revered figure in the world of Taoist arts, famously said, “The slowest is the fastest.” This paradoxical statement reveals a profound truth about the nature of learning and mastery in Taoist practices like Tai Chi. By adopting slow, deliberate movements, we engage deeply with the process, learning more efficiently and thoroughly. This deliberate pace allows for precision and acuity in learning, ensuring that movements are not just performed but are understood and internalized.

Furthermore, slow movement bridges the gap between the conscious and the unconscious mind. When we move slowly and with focus, we tap into our unconscious, enabling us to learn at a deeper level. This connection not only accelerates learning but also ensures that when rapid movement is necessary, it can be executed swiftly and effortlessly, unhindered by overthinking. This principle mirrors practices in music and other disciplines, where mastering slow, deliberate practice leads to the ability to perform complex actions at speed.

In the context of Tai Chi and Qigong, this focus on slow movement is not merely a physical exercise; it is a cultivation of qi, or life energy. Unlike concepts of muscle memory, which are rooted in physical repetition, the practice of Tai Chi emphasizes the flow and control of this vital energy. The movements, though outwardly slow, are internally vibrant, facilitating the circulation of qi throughout the body and promoting health, vitality, and a deep sense of inner balance.

This approach to movement and learning underscores the holistic nature of Taoist practices, where the journey of mastery involves the integration of body, mind, and spirit, moving beyond the physical to touch the essence of our being.

Delving into the realm of science, the benefits of slow movement, as practiced in Tai Chi and similar Taoist arts, find strong support in contemporary research. This body of evidence highlights the physical advantages and the profound mental and emotional impacts of engaging in slow, deliberate movements.

Slow movement practices have been shown to improve motor control by enhancing the neural pathways involved in movement coordination. This fine-tuning of motor skills is crucial not only for physical agility but also for preventing falls, especially in older adults. Furthermore, the emphasis on slow, controlled movements aids in developing a deep, intuitive understanding of one’s body, leading to improved posture and movement efficiency.

On a mental and emotional level, engaging in slow-movement practices encourages a state of focused awareness. This state, achieved by harmonizing movement with breath, has been linked to reduced stress levels and anxiety, promoting a sense of calm and well-being. Moreover, this focused state facilitates a meditative mindset, where the mind can achieve clarity and distractions are minimized. This clarity of mind is not only beneficial for mental health but also enhances cognitive function, including attention span and memory retention.

The practice of slow movement, therefore, acts as a bridge between the physical and the mental, offering a comprehensive approach to well-being. By encouraging the practitioner to move with intention and awareness, these practices cultivate an environment where the body can relax, the mind can clear, and the spirit can flourish. This holistic benefit package aligns perfectly with the Taoist view of health and harmony, emphasizing the importance of balance in all aspects of life.

Moreover, the internal focus on qi movement within these practices offers insights into the energetic dimensions of health. Unlike the purely physical perspective of exercise, slow movement in Taoism seeks to balance and enhance the flow of life energy throughout the body. This energetic approach provides a deeper level of healing and rejuvenation, addressing the symptoms of imbalance and the root causes, fostering a profound sense of vitality and inner peace.

Tai Chi, often described as meditation in motion, exemplifies the essence of slow movement within the Taoist tradition. As a martial art, it transcends the physicality of movement, embedding profound philosophical and energetic principles into each form and posture. Tai Chi’s practice vividly illustrates the adage “The slowest is the fastest,” showcasing how deliberate, mindful movements can lead to rapid internal growth and external proficiency.

The foundational practice of Tai Chi involves a series of movements performed with grace, precision, and fluidity, emphasizing the flow of qi, or life energy, throughout the body. This slow, intentional movement cultivates a deep connection between the mind, body, and spirit, allowing practitioners to achieve a state of inner stillness amidst motion. This paradoxical state of moving stillness is where the practitioner can access heightened levels of awareness and acuity, tapping into the deeper realms of consciousness and the unconscious.

One of the key benefits of Tai Chi as a slow-movement practice is its ability to improve physical health through strengthening the cardiovascular system, enhancing balance and flexibility, and reducing stress-related ailments. But beyond these tangible benefits, Tai Chi offers a pathway to spiritual enlightenment, embodying the Taoist pursuit of harmony between humanity and the natural world.

The practice of Tai Chi also illustrates that by slowing down, we can engage more fully with the present moment, allowing for a richer, more nuanced experience of life. In the context of learning and mastery, Tai Chi teaches that patience, persistence, and a focus on the journey rather than the destination are essential. This approach fosters the development of physical skills and the cultivation of virtues such as humility, respect, and compassion.

Furthermore, Tai Chi’s emphasis on the flow of qi highlights the distinction between the energetic focus of Taoist practices and the purely physical focus seen in many other forms of exercise. This energetic perspective offers insights into the interconnectedness of all life and the universe, providing a holistic approach to health and well-being that transcends physical boundaries.

Integrating slow movement principles into daily life offers a pathway to enhanced well-being accessible to everyone, regardless of age, fitness level, or background. The essence of these practices—whether through Tai Chi, Qigong, or simple mindful exercises—lies in their ability to foster a deeper connection with oneself and the surrounding world through deliberate, attentive movements.

Starting with Slow Movement Practices For those new to slow movement, the journey begins with recognising the value of slowing down. This can be as simple as dedicating a few moments each day to moving with intention and awareness, whether through performing daily tasks, walking, or engaging in specific exercises designed to cultivate mindfulness and presence.

Incorporating Tai Chi and Qigong into Your Routine Tai Chi and Qigong offer structured ways to practice slow movement, with routines that range from simple to complex, catering to all levels of experience. Beginners can start with basic Qigong breathing exercises and simple Tai Chi forms, gradually building up to more intricate sequences as their understanding and skill develop. These practices do not require special equipment or a large space, making them adaptable to most living environments.

Focusing on Breath and Movement Integration A key aspect of slow-movement practices is integrating breath with movement. This focus on breathing helps to regulate the flow of qi, or life energy, enhancing the health benefits of the exercises and promoting a state of calm and centeredness. By paying attention to the breath, practitioners can deepen their connection to their bodies and the present moment, elevating the practice from mere physical exercise to a holistic spiritual discipline.

Applying Slow Movement Principles to Everyday Life The slow movement principles can extend beyond formal practice into everyday activities. By adopting a mindful approach to daily tasks—paying attention to the sensations of movement, the rhythm of breath, and the quality of one’s attention—individuals can transform mundane activities into opportunities for presence and mindfulness. This approach not only enriches the quality of everyday life but also reinforces the practice of wu wei, acting effortlessly by the natural flow of life.

Challenges and Patience Embracing slow movement requires patience and persistence, especially in a world that often values speed and efficiency over depth and quality. The challenge for practitioners is to remain committed to the path, recognizing that the benefits of these practices unfold over time. This development’s gradual nature is a lesson in patience and trust in the process, reflecting the Taoist understanding that true growth and understanding emerge from a foundation of gentle, consistent effort.

In conclusion, the practical application of slow movement principles offers a profound way to enhance physical, mental, and spiritual well-being. By integrating these practices into daily life, individuals can discover a deeper sense of peace, balance, and harmony, embodying the Taoist ideal of living following the natural rhythms of the universe.

The World Institute of Slowness promotes a philosophy that advocates for slowing down life’s pace to enhance well-being, productivity, and happiness. It emphasizes a new way of thinking about time, aiming to make individuals healthier and more content by encouraging a slower approach to life’s activities. Their vision aligns with the benefits of slow-movement practices, suggesting that slowing down is beneficial and essential for a fulfilling life. For more detailed insights and to explore their initiatives, visit their website at https://www.theworldinstituteofslowness.com/.

In today’s fast-paced professional world, the ability to make timely and effective decisions is paramount. Yet, many professionals find themselves trapped in a cycle of overthinking, leading to a state commonly referred to as analysis paralysis. This phenomenon occurs when an individual becomes so lost in the details and potential outcomes of a decision that they are unable to take action. The roots of this issue can often be traced back to a disconnection from the present moment, a principle that is central to Taoist philosophy.

Taoism, a philosophical tradition of Chinese origin, emphasizes living in harmony with the Tao, the Way or path, the fundamental nature of the universe. A key aspect of this philosophy is the concept of living in the now, which is crucial for making timely decisions. Tai Chi, a martial art deeply rooted in Taoist principles, offers a practical pathway out of the quagmire of overthinking. Through its slow, deliberate movements and emphasis on awareness and focus, Tai Chi teaches practitioners to anchor themselves in the present moment, thereby enhancing decision-making capabilities.

Taoist philosophy offers timeless wisdom on the nature of existence and the path to harmony. Central to Taoism is the concept of the Tao, often translated as “the Way,” which signifies the ultimate creative principle of the universe. This principle advocates for a life of simplicity, spontaneity, and harmony with nature, emphasizing the importance of aligning oneself with the natural flow of life. In the context of decision-making, this means fostering an ability to act effortlessly and intuitively, guided by the natural course of events rather than forced analysis and deliberation.

Tai Chi, as a physical embodiment of Taoist principles, serves as both a martial art and a meditative practice. It teaches the practitioner to move with softness and fluidity, embodying the concept of Wu Wei, or “non-action.” Wu Wei does not imply inaction but rather taking action that is in perfect harmony with the natural world, minimizing effort and resistance. Through the practice of Tai Chi, individuals learn to apply these principles to their daily lives, including their professional decision-making processes.

The movements in Tai Chi are designed to cultivate qi, or life energy, and promote its smooth flow throughout the body. This cultivation of energy not only enhances physical health but also mental and emotional well-being. By focusing on the breath and the precise execution of movements, practitioners develop a heightened state of awareness and acuity, anchoring themselves firmly in the present moment. This focused state of mind is antithetical to overthinking and analysis paralysis, as it encourages a connection with the intuitive wisdom that lies beyond rational thought.

In professional settings, adopting a Taoist approach to decision-making means learning to trust this intuitive process, and recognizing that enough is enough, and not all decisions require exhaustive analysis. It involves understanding the difference between necessary deliberation and the point at which further analysis yields diminishing returns and can even have a detrimental effect. Tai Chi, by nurturing an awareness of this balance, offers a practical tool for professionals to develop the clarity and focus needed to navigate complex decisions with ease and confidence.

By integrating the principles of Taoist philosophy through the practice of Tai Chi, individuals can transcend the limitations of conventional decision-making strategies. This section has explored the foundational concepts of Taoism and how Tai Chi serves as a conduit for these principles, promoting a way of being that is in harmony with the natural order.

In the framework of Chinese Medicine, which shares its roots with Taoist philosophy, the concept of the Five Elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water) is pivotal. Each element is associated with different aspects of physical and emotional well-being. The Earth element, in particular, is often linked to the spleen and stomach, governing digestion and the transformation of food into energy. On an emotional level, the Earth element corresponds to thought, reflection, and sympathy. While these qualities are essential for analytical thinking and empathy, an imbalance in the Earth element can lead to overthinking, worry, and rumination—traits that are counterproductive in the context of decision-making.

Tai Chi practice offers a holistic approach to rebalancing the Earth element, thus mitigating the tendency toward overthinking. By engaging in the slow, deliberate movements of Tai Chi, practitioners cultivate a state of meditative focus that transcends the analytical mind. This focused state encourages a connection with the body and the present moment, drawing attention away from the cyclic patterns of thought that characterize overanalysis. The rhythmic breathing and movement patterns of Tai Chi help to harmonize the body’s energy, promoting mental clarity and emotional stability.

This meditative aspect of Tai Chi is crucial. The practice teaches how to maintain a clear, focused mind, one that can navigate the complexities of professional challenges without succumbing to the paralysis of overanalysis. By fostering a state of calm attentiveness, Tai Chi enables practitioners to approach decisions with a balanced perspective, recognizing when enough information has been considered and when it is time to act.

Moreover, Tai Chi’s emphasis on cultivating internal energy (qi) and maintaining its smooth flow throughout the body plays a significant role in enhancing cognitive function and emotional resilience. This energetic balance is conducive to a mindset that values efficiency and efficacy over exhaustive deliberation. It supports the development of an intuitive sense of timing and appropriateness in decision-making, aligning actions with the natural flow of circumstances.

Tai Chi is not just a series of individual movements; it is a continuous flow that mirrors the dynamic processes of the natural world. The essence of Tai Chi encourages a mindset that is always in motion, always ready to adapt and move forward. This section explores how the timing, synchronization, and fluidity inherent in Tai Chi forms foster dynamic thought processes, crucial for effective decision-making.

In the practice of Tai Chi, each movement flows seamlessly into the next, with practitioners required to maintain a constant awareness of their body, breath, and mind. This requirement for synchronization not only with one’s own movements but also with those of the instructor and fellow practitioners cultivates an acute sense of timing and rhythm. Such synchronization demands presence—being fully in the moment, and responsive to the subtle shifts and changes in the environment.

This translates into an ability to stay attuned to the evolving dynamics of the workplace, industry trends, and team interactions. The fluidity and adaptability practised in Tai Chi can help counter the rigidity of overanalysis by promoting a more flexible approach to problem-solving and decision-making. Instead of becoming fixated on a single point of view or bogged down by the fear of making the wrong decision, practitioners learn to flow with the circumstances, adapting their strategies as needed.

The continuous movement of Tai Chi symbolizes the principle of progress and evolution. By engaging in a practice that never truly stops but rather transitions smoothly from one form to the next, practitioners embody the idea of continuous forward motion. This physical embodiment of progress encourages a similar approach to thought processes—thinking that is not static but dynamic, always ready to evolve based on new information or changes in context.

In the professional realm, this means developing the confidence to make decisions even when not all information is available or when the outcome is uncertain. Tai Chi teaches that hesitation or stagnation is contrary to the natural flow of life. Instead, by adopting a mindset of continuous movement and improvement, professionals can learn to make decisions that are timely and informed by the present moment, rather than delayed by the pursuit of absolute certainty.

Through the practice of Tai Chi, professionals can cultivate a dynamic thought process that values progress and adaptability. This approach is antithetical to analysis paralysis, which is characterized by static thinking and indecision. By learning to embrace the fluidity, synchronization, and forward motion inherent in Tai Chi, individuals can develop a more efficient and effective decision-making style.

Tai Chi is often practised as a solo endeavour, focusing on individual forms and meditation to cultivate qi and internal strength. However, a significant aspect of Tai Chi training involves partner exercises such as “sticky hands” (Yifou Shou), which can offer profound insights into the dynamics of interaction, balance, and real-time responsiveness. These exercises are particularly effective in teaching practitioners how to maintain focus, adaptability, and presence in the moment—qualities that are invaluable for professionals seeking to overcome analysis paralysis.

Sticky hands is a practice wherein two partners maintain constant contact with each other’s hands while moving in a circular way, sensing and manipulating the balance and force of the other without losing their own centre. This exercise emphasizes sensitivity, relaxation, and the flow of energy between participants. It requires a high level of awareness and the ability to respond to subtle shifts in movement and pressure without preconception or delay.

The lessons we learn from sticky hands can be practically integrated into all kinds of real-world situations. Just as the exercise requires staying present and responding to the immediate conditions without overthinking, effective decision-making demands an awareness of the current situation and the flexibility to adapt as circumstances evolve. The practice teaches the value of responding to challenges and opportunities as they arise, rather than becoming mired in hypothetical outcomes or excessive planning.

Partner exercises in Tai Chi foster a mindset that is always alert and adaptable, ready to shift direction or strategy in response to new information. This mindset is crucial in a professional context, where conditions can change rapidly and decisions may need to be revisited or revised based on unfolding events. By training to stay connected and responsive to a partner’s movements, practitioners learn the importance of maintaining a dynamic approach to problem-solving and decision-making, one that is rooted in the present rather than fixated on past analyses or future uncertainties.

The continuous engagement required in partner exercises cultivates a deep sense of presence, pulling the practitioner’s attention away from distracting thoughts and towards the immediate experience. This focus on the present moment is a powerful antidote to analysis paralysis, which often stems from an overemphasis on predicting and controlling future outcomes. By learning to centre themselves in the now, professionals can enhance their capacity for clear, focused decision-making, unencumbered by the weight of unnecessary deliberation.

Tai Chi, through its solo forms and partner exercises like sticky hands, offers a comprehensive approach to overcoming analysis paralysis. By embodying the principles of adaptability, responsiveness, and presence, professionals can navigate the complexities of their roles with greater ease and efficiency. The practice encourages a shift from static, overanalytical thinking to a more dynamic, intuitive approach to decision-making, one that is aligned with the natural flow of life.

As we integrate these lessons from Tai Chi into our professional lives, we open ourselves to a more harmonious and effective way of working. The path laid out by Tai Chi, rooted in the ancient wisdom of Taoist philosophy, offers not just a strategy for better decision-making, but a way of living that is in deeper alignment with the natural world and our innate capacities.

Tai Chi encourages an alignment with the Taoist concept of Wu Wei, or effortless action, which is especially relevant in today’s professional environment where the pressure to perform can lead to overthinking and decision-making inertia. By embracing the lessons of Tai Chi, professionals can learn to trust in the natural course of actions, relying on intuition and informed spontaneity rather than falling prey to the paralysis of over-analysis.

To begin integrating Tai Chi into professional life, it’s essential to start with small, consistent practices. This could involve dedicating a few minutes each day to Tai Chi exercises, focusing on breath work and the fluidity of movements, or engaging in awareness practices that emphasize presence and awareness. Workshops or classes led by experienced Tai Chi practitioners can provide valuable guidance and support for those new to the practice.

Professionals can also apply the principles of Tai Chi to their decision-making processes directly by:

The integration of Tai Chi into professional life has the potential to not only enhance individual decision-making capabilities but also to contribute to a more balanced and harmonious workplace culture. As more individuals adopt this approach, the collective mindset can shift towards one that values mindfulness, adaptability, and efficiency, creating an environment where creativity and productivity flourish.

The benefits of Tai Chi, both for overcoming analysis paralysis and for overall well-being, are cumulative and deepen with regular practice. It is a journey of continuous learning and growth, where each step brings a deeper understanding of oneself and the Taoist principles that underpin this ancient art. Professionals are encouraged to view Tai Chi not just as a tool for better decision-making, but as a lifelong practice that offers insights into living a balanced, harmonious life.

By embracing Tai Chi and its Taoist roots, professionals can navigate the complexities of their careers with greater ease, making decisions that are not only effective but also aligned with the natural flow of life. In doing so, they open themselves to a world where action arises not from force or fear, but from a place of balance, clarity, and harmony.

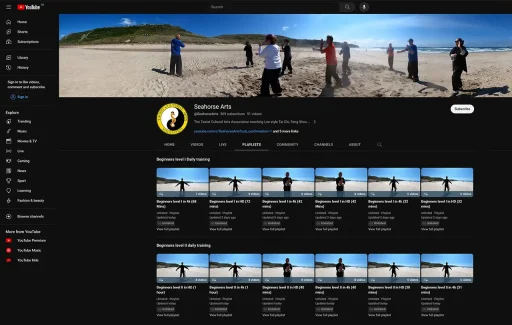

Have a go at our daily training Youtube Playlists. We have Beginners level I and II video playlists and a variety of options for you to choose from.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel to get notified of the latest uploads

Just as the Lotus flower opens with the rising of the sun your energy can be awakened each day with our program of Qigong and Tai Chi exercises. Qi flows best when the body relaxes so we start you off with loosening up first of all, then comes a deep breathing or Daoyin exercise to awaken your primary energy centre located in the lower abdomen and known as the Dantian.

The next stage is Kai Men or opening the door which activates your meridians to let the energy flow. Then we take you through a Yang or flowing movement form known as the Tiaowu or Tai Chi dance. Then comes the more meditative Tai Chi form.

As we near the end of the session another deep breathing exercise known as the Five Lotus Blossoms returns your energy to the centre where it can be stored until you need it.

Are you ready to unlock the hidden potential within you? Discover the transformative power of Tai Chi and Qigong exercises, and watch as your life takes on a vibrant new hue.

Imagine a daily routine that not only boosts your physical flexibility and stamina but also enhances your mental prowess and uplifts your overall mood and sense of purpose in life. As you begin this journey, you’ll feel a surge in acuity and awareness, and a warm, invigorating energy flowing through every fiber of your being. This is the secret that awaits you.

But here’s the magic: this isn’t a fleeting experience. With consistent practice, you’ll notice that these uplifting moments gradually transform into sustained energy levels that grow day by day. Your awareness sharpens, and you gain control over your energy, ensuring it’s at your disposal when needed and comfortably stored away when it’s not.

The essence of Taoist energy training methods is now within your reach. Don’t wait any longer – start your transformation today and take it to the next level.

Before we explore how Tai Chi can ease pain, let’s first understand what Tai Chi is. Tai Chi, also known as Tai Chi Chuan or Taijiquan, is a Chinese practice that combines slow, graceful movements, deep breathing, and meditation. It’s been around for over 2,000 years and aims to improve both physical and mental well-being.

In Tai Chi, there’s a fundamental concept called Qi (pronounced “chee”). In Chinese medicine, Qi is thought to be the vital energy that flows through the body, keeping us healthy. When there are blockages or imbalances in the flow of Qi, it can lead to physical and mental health issues, including pain.

According to Chinese medicine, pain can occur when Qi is blocked. Tai Chi, with its slow and deliberate movements, is designed to remove these blockages and restore the natural flow of Qi. Here’s how Tai Chi does that:

Tai Chi’s ability to relieve pain isn’t just anecdotal; it’s backed by science. Here are ten ways Tai Chi can help with pain:

In a world grappling with opioid addiction, Tai Chi offers a safer approach to pain management. Opioids can be effective for pain but come with side effects and a high risk of addiction. Tai Chi, however, addresses the root causes of pain without these risks. It empowers individuals to manage pain naturally.

Pain isn’t just physical; it has psychological dimensions. Tai Chi recognizes this and can alleviate psychological symptoms often linked to chronic pain:

Tai Chi, rooted in traditional Chinese medicine and focused on Qi flow, offers a holistic approach to pain relief. Scientific research supports its effectiveness for both physical and psychological aspects of pain. Choosing Tai Chi over opioids and other medications empowers you to tap into your body’s natural healing abilities while avoiding addiction risks. If you’re ready to embark on a pain-free journey and improve your well-being, consider joining our Tai Chi classes. Explore the wisdom of Tai Chi and experience the power of Qi. Say goodbye to pain and hello to a healthier you.

ITN ‘Tonight‘ visited us to capture footage of our Summer Course at Sennen Beach for their documentary, ‘Britain on Painkillers.’ This documentary explores alternative approaches to opioids. During their visit, they conducted interviews with some of our students who have found success in using Tai Chi as an alternative method for pain relief.

Notably, one of our students, who was prominently featured in the documentary, has taken a significant step forward. He has established his own Tai Chi club in his hometown, a development that garnered attention and led to a featured interview on BBC Radio Cornwall. You can watch this inspiring interview on YouTube.

The cultural annals of China stand testament to an intricate interweaving of wisdom and philosophy. Amongst this vast body of knowledge, ‘yang’ emerges as a beacon, illuminating the realms of life, medicine, and physical harmony. This guiding principle, celebrated for its vibrant energy and warmth, remains a cornerstone of Chinese thought. Through this comprehensive treatise, we will embark on an exploration of yang—drawing inspiration from Taoist sages, demystifying its role in Chinese medicine, and understanding its manifestation in the art of Tai Chi.

Taoism, with its origins tracing back millennia, has etched a unique space in the world of philosophical thought. Central to this is the concept of yin and yang—a harmonious dance of opposites.

Laozi, one of Taoism’s foundational figures, provided profound insights into the nature of yang. In his seminal work, the Dao De Jing, he articulates:

“The Way gives birth to One,

One gives birth to Two,

Two gives birth to Three,

Three gives birth to all things.”

[Source: Dao De Jing]

This passage is often interpreted as a reference to the progression from Tao (the Way) to the duality of yin and yang and then to the myriad things of the world. Here, yang emerges as the active, shining counterpart to the passive yin.

Zhuangzi, another pillar of Taoist thought, often delved into the intricacies of yang. He stated:

“There is a beginning. There is a not yet beginning to be a beginning. There is a not yet beginning to be a not yet beginning to be a beginning. There is being. There is nonbeing.”

[Source: Zhuangzi]

This poetic meditation further emphasizes the intertwined nature of yin and yang, the existence and non-existence that play together in the universe.

Liezi, another eminent Taoist philosopher, built upon this foundation, often emphasizing balance and harmony.

The iconic yin-yang emblem, with its entwined black and white motifs, stands as a visual testament to the Taoist worldview. Its genesis lies in ancient China, representing the cyclical dance of day and night, activity and passivity, yang and yin. The yang, depicted in bright white, symbolizes daylight, warmth, and spirited activity—a harmonious counterbalance to yin’s tranquil darkness.

In the universe of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), yang is heralded as the beacon of activity, warmth, energy, and motivation.

Where yin is about conservation and nourishment, yang epitomizes the radiance of life. It’s the vital force that drives bodily functions, keeps the blood warm, and fuels the mind’s motivations. Diseases marked by excessive heat, feverishness, inflammation, or hyperactivity signal an imbalance where yang predominates.

Yet, yang’s significance lies not just in its standalone might but in its role to counterbalance yin. For instance, where yin represents cold and stagnation, yang provides the warmth and movement essential to maintain harmony.

Tai Chi, the poetic symphony of movements, is a vibrant playground where yin and yang dance. Yang, in this realm, is about the outward expression of energy. It’s the crescendo in the rhythmic flow of Tai Chi—where movements peak in their expressiveness.

However, every Tai Chi sequence begins in the stillness of yin and culminates back into it, making yang the dominant force in between—much like life, which starts and ends in stillness, with a burst of energy and activity in the middle.

In essence, yang stands as a beacon, a testament to life’s vibrant energies. Whether through the meditative verses of Taoist sages, the healing touch of Chinese medicine, or the expressive dance of Tai Chi, it continues to guide, enlighten, and energize humanity in its timeless journey.

In the vast tapestry of Chinese philosophy and medicine, few concepts are as integral and profound as yin. Rooted deeply in the country’s ancient cultural and spiritual traditions, yin offers an enlightening perspective on balance, harmony, and health. When one delves into Tai Chi, the art of graceful movement and meditation, the significance of yin becomes even more pronounced. Let’s embark on a journey to comprehend the depths of yin and its pivotal role in Tai Chi training.

Yin: at its most basic, represents the passive, cool, and dark aspect of things. It stands in contrast to yang, its counterpart, which symbolizes the active, warm, and bright facets of existence. Together, they paint a picture of dualism, where every element possesses both yin and yang characteristics in varying proportions.

In Chinese medicine, this dualistic interplay forms the cornerstone of understanding health and illness. Balance is the key; ailments arise when there’s a disruption in the equilibrium of yin and yang within the body. Therefore, treatments often aim at restoring this balance.

For instance, a person suffering from fatigue, cold limbs, and a pale complexion may be diagnosed as having a yin deficiency. The goal, then, would be to replenish the body’s yin energy, often through herbs, acupuncture, or dietary changes.

The nourishing quality of yin is indispensable in Chinese medicine. Think of yin as the nurturing, moistening force that keeps bodily tissues healthy and supple. Without sufficient yin, the body could become dry, brittle, and susceptible to various ailments.

This is not merely about hydration or nutrition. It’s about the body’s innate ability to maintain its structures, functions, and vitality. In other words, yin is the sustaining force that provides the groundwork for yang’s dynamic actions.

Tai Chi, often described as meditation in motion, embodies the principles of yin and yang in every movement. But what role does yin specifically play in this practice?

While our focus here is yin, it’s essential to appreciate that in Tai Chi, yin never exists in isolation. Every movement, every breath, every intention weaves yin and yang together in a dance of harmony. As practitioners deepen their understanding of yin, they simultaneously grasp the essence of yang. The two are inextricably linked, and it’s this union that brings about the profound benefits of Tai Chi.

In our modern, fast-paced world, the ancient wisdom of yin offers a refreshing perspective on balance, health, and well-being. Its teachings remind us of the importance of nurturing, grounding, and looking inward. Whether you’re exploring Chinese medicine or immersing yourself in Tai Chi training, understanding and embracing yin can open doors to deeper self-awareness, healing, and harmony.

Tao, a word often spoken but perhaps less understood, stands as a pillar of Chinese philosophy and spirituality. Have you ever wondered about those moments when everything seems to click into place? When there’s an inexplicable harmony in the chaos of life? That, my friend, is a touch of the Tao. If you’re someone who has dipped their toes in the vast ocean of spirituality or holistic health, or even if you’re a curious newcomer, this guide aims to shine a light on the Tao, its underlying principles, and its profound connection to Tai Chi.

For millennia, Chinese medicine has been more than just remedies and treatments. It’s a holistic view of health, encapsulating mind, body, and spirit. And at the heart of this ancient knowledge lies the philosophy of Tao. But to truly grasp the essence of the Tao, one must first delve into the dual concepts of Yin and Yang.

Imagine a silent, tranquil night where the world is at rest. Picture the moon’s soft glow, the gentle embrace of darkness, and the world recharging for a new day. This is the realm of Yin – calm, passive, and restorative.

In Chinese medicine, Yin is often visualized as the shaded side of a mountain. It’s cool, mysterious, and nurturing. It represents all things receptive, cool, and internally focused. Qualities like intuition, rest, and reflection are hallmarks of Yin energy.

From a medicinal standpoint, Yin is incredibly essential. Why, you ask? Because Yin, with its nourishing properties, ensures our body’s internal systems function smoothly. It hydrates our tissues, cools our internal temperature, and provides a deep, rejuvenating rest to our organs. It’s like the deep recuperative sleep we crave after a long, tiring day.

To further paint a picture, think of your body as a machine. Yin would be the coolant, ensuring the engine doesn’t overheat. It’s the oil ensuring everything runs smoothly. Without adequate Yin, our bodies can experience dehydration, overheating, or excessive restlessness.

Now, after that peaceful night, visualize the break of dawn. The radiant sun stretching its rays, the world waking up, and a surge of energy making everything come alive. That’s Yang – dynamic, fiery, and active.

In the grand tapestry of Chinese medicine, Yang is akin to the sunlit side of a mountain. It’s warm, bright, and externally driven. It encompasses all things active, warm, and outward-moving. When you’re motivated, bursting with energy, or when your metabolism is running high, that’s Yang energy at play.

In the body, Yang acts as the driving force. It’s the spark that ignites our actions, the warmth that circulates our blood, and the energy that powers our day-to-day activities. It’s that burst of adrenaline you feel before an intense workout, and the heat you generate during physical exertion.

But as beautiful as Yang energy sounds, an excess can lead to burnout. Just as a machine can get overworked, so can our bodies. And when there’s too much Yang, we may experience inflammation, high blood pressure, and a restless mind.

Life thrives on balance. Day and night, activity and rest, warmth and coolness. This duality is what keeps the universe, and us, in harmony. Yin and Yang, with their contrasting qualities, might seem like opposites, but they’re two sides of the same coin. In fact if you look closely at the Yin-Yang symbol you will see that in the middle fo each section is a dot of the opposite colour. What this means is that Yin and Yang are part of a cycle, when one reaches the extreme it turns to it’s opposite. The maximum swing of the pendulum is exactly when it starts to change to the opposite direction and swing back again. Think of Midsummer’s Day, it is the peak of Summer, and yet it is the first day when the nights start closing in again so in a way it is the start of Winter. Conversely the same principle applies to the midwinter solstice, it is the time of maximum Yin but it is also the first day when Yang begins to rise and the days start getting longer again. This is a basic principle in Taoist philosophy and can be exemplified in Tai Chi practice which is based on Taoism, for example when you stand on tiptoe you become unstable and although momentarily you become taller then it is also more likely that you will fall onto the ground and become smaller and more vulnerable. The same is true if you think about midnight and midday. The same principle is also at work in the body, if you become hotter you become more and more active or Yang until you become so hot that you actually pass out and become completely inactive. Conversely, as you become cold you become more and more inactive until you get so cold you have to start rubbing your hands together and moving around to generate some heat.

Together, Yin and Yang regulate each other, and they ensure our body, mind, and spirit remain in equilibrium. A disruption in this balance can lead to health issues, mental unrest, and emotional imbalances.

Enter Tai Chi – an ancient martial art form that’s more than just self-defense. It’s a dance of energies, a physical manifestation of the Tao, and a way to maintain the delicate balance of Yin and Yang in our lives.

Our Tai Chi club welcomes all who wish to experience this harmony firsthand. As you learn the fluid movements of Tai Chi, you’re not just engaging in physical activity; you’re embarking on a journey of self-awareness, balance, and health.

Especially when we talk about liver function and the flow of Qi (life energy), Tai Chi emerges as a guardian. The liver, in Chinese medicine, is the chief officer of Qi flow. Through Tai Chi, one ensures this officer is always alert, directing Qi seamlessly throughout the body, preventing any blockages or imbalances.

Understanding the Tao, Yin, Yang, and Tai Chi is like unlocking the secrets to a balanced life. It’s the guidebook to holistic health and a fulfilled existence. Joining our Tai Chi club is not merely about mastering an art form; it’s about embracing a philosophy that has stood the test of time. Dive deep, explore the dance of energies, and let every move, every breath, resonate with the universe’s rhythm.

By tapping into the ancient wisdom of the Tao, Yin, Yang, and Tai Chi, you’re not only enhancing your health but also enriching your soul. Ready to embark on this journey? Our Tai Chi club awaits!

In Western medicine, anxiety is understood as a mental health disorder characterized by a consistent state of apprehension, persistent fear, or excessive worry about everyday situations. This condition can manifest through various symptoms including racing heart, rapid breathing, sweating, brain fog, lack of focus, indecision and chronic fatigue, significantly affecting an individual’s quality of life.

The roots of anxiety lie in the brain’s amygdala, a critical structure that processes our fear and emotional responses. When one faces a perceived threat, the amygdala triggers a cascade of reactions, releasing stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, thus initiating the fight-or-flight response. In a state of anxiety, the amygdala may become overactive, causing an imbalance in these responses. This condition often forms a vicious cycle, with each anxious thought activating the amygdala and releasing stress hormones, which in turn amplifies feelings of fear and worry.

Treatment in Western medicine usually involves pharmaceutical interventions, cognitive-behavioural therapies, and various lifestyle modifications. The objective is to alleviate the physical symptoms, modify the thought process, and prevent anxiety from escalating into severe conditions such as panic attacks, generalised anxiety disorder, or phobias.

Ancient Chinese medicine offers an entirely different perspective on anxiety, grounding its interpretation in the philosophy of the Five Elements: Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water. Each element is associated with specific emotions, organ systems, and aspects of the psyche, creating a holistic view of health and wellness.

Anxiety, in this philosophy, is linked predominantly with fear and is associated with the Water element. This element corresponds with winter, a time of introspection, conservation, and preparation for new growth. Analogous to the stillness of a frozen lake, the Water element encourages inner reflection, deep wisdom, and emotional resilience.

At times, fear can serve a useful purpose. It can heighten our awareness, making us cautious when we approach potentially dangerous situations, such as a dark alleyway. Fear, when properly channeled, can act as a warning system, alerting us to impending risks.

However, it becomes problematic when this emotion starts to overtake our lives, manifesting as incessant worries or obsessive fears. This excessive activation of fear signals an imbalance that needs to be addressed and rectified.

In the context of the Water element in Chinese medicine, fear is a constituent emotion. When fear becomes overpowering, it can be likened to a tumultuous wave sweeping us off our feet. This overwhelming sensation can cause us to lose our rootedness and connection with our surroundings, akin to not being able to feel the ground beneath us.

Such intense fear can lead to a state of emotional and physical paralysis, making us vulnerable to external and internal threats. Thus, recognizing and managing the overactivity of fear is a crucial step towards achieving emotional balance and overall wellbeing.

Water is associated with the kidneys and bladder, which form a Zang-Fu pair in the system of Chinese medicine. Zang organs are perceived as Yin, storing and preserving vital substances, while Fu organs are Yang, responsible for digesting food and transmitting nutrients.

The kidneys, considered the “Root of Life,” hold a significant role in this system. They are the storehouse of “Jing” or “Essence,” a crucial substance in the body. Jing is inherited from our parents at conception, and while a small portion can be acquired through diet and lifestyle, it is largely finite, slowly depleting over a lifetime.

Jing is a fundamental concept in Chinese medicine. It provides the basis for all of our body’s functions, growth, reproduction, and development. It is often associated with aging, as it influences our constitutional strength and resilience, dictating the pace at which we grow, mature, and eventually decline.

In the context of anxiety, a deficiency in Kidney Yin, or Jing, can lead to an imbalance in the Water element, resulting in irrational fear and constant worry. This depletion of Jing disrupts the body’s equilibrium, manifesting as a variety of physical and psychological symptoms.

Kidney Yin deficiency can be influenced by various lifestyle factors that deplete the body’s Jing. These include excessive sexual activity, long-term use of drugs or medication, chronic stress, overworking, unhealthy dietary habits, and an imbalanced lifestyle.

Stimulants like coffee, tea, sugar, alcohol, food additives, and toxins in the environment can hyperstimulate the metabolism and exhaust the kidney’s resources, depleting Jing. Furthermore, poor lifestyle choices and bad habits can become a burden on the system, causing a strain on the kidneys and leading to a Jing deficiency.

Managing Kidney Yin deficiency and thus, anxiety, involves significant lifestyle adjustments. Reducing deleterious activities and improving diet are essential steps. However, more proactive measures can be taken to correct the imbalance and restore Jing.

Tai Chi, an ancient Chinese martial art form, stands at the intersection of these remedial steps. Practising Tai Chi promotes deep, regulated breathing, fluid body movements, and a meditative mindset, creating a synergy that encourages balance and harmony.

Tai Chi integrates Wuwei or effortless action into physical movement, promoting a relaxed but focused state of mind that minimizes anxiety and stress. The practice encourages the conservation of Jing, allowing for the preservation and rejuvenation of the body’s vital resources.

In addition, Tai Chi cultivates willpower and resilience. Consistent practice nurtures mental strength, enabling practitioners to combat stress, anxiety, and fear more effectively. The holistic benefits of Tai Chi — physical, mental, and emotional — foster an inner peace that helps manage and potentially overcome anxiety.

In conclusion, anxiety is a complex condition that can be interpreted and addressed from both Western and Eastern medical perspectives. While lifestyle changes and mindfulness practices form the cornerstone of managing anxiety, integrating practices like Tai Chi can further enhance the body’s ability to maintain balance and harmony, offering a powerful approach to combat anxiety.

While Tai Chi is a concentrated and meditative practice, it is also a martial art, with deep roots in self-defence. Integrating Tai Chi’s self-defence training into your routine offers another dimension in alleviating anxiety. This practice enhances physical capabilities and instills a sense of safety, confidence, and empowerment that can extend beyond the training environment into everyday life.

When we feel safe and capable, we naturally exude confidence. This confidence can influence the way we navigate our daily lives, from how we carry ourselves physically to how we engage in social situations. An improved physical stance can project self-assuredness, deter potential threats, and encourage positive interactions.

In the realm of social anxiety, this confidence plays a crucial role. The fear of judgment, embarrassment, or rejection in social situations can trigger anxiety. However, by bolstering self-esteem and confidence through self-defence training, these fears can be significantly mitigated.

At the heart of self-defence training in Tai Chi is the principle of balance and control. By learning how to maintain physical and emotional stability even under pressure, individuals can apply these skills in a social context. This practice enables them to manage stressful interactions more effectively, thereby reducing feelings of anxiety. This kind of training provides tangible demonstrations of enhancing self-preservation skills through practical methods, which consequently serve to boost confidence.

Moreover, the social aspect of Tai Chi training also provides a supportive community. This interaction, while offering an opportunity for communal learning and growth, can serve as a safe space for individuals with social anxiety to gradually build their comfort in interacting with others.

Tai Chi, by integrating mindfulness, physical resilience, and self-defence skills, forms a holistic approach to combating anxiety. It’s not just about managing symptoms; it’s about empowering individuals to take control, foster inner strength, and lead a balanced, harmonious life.

In essence, overcoming anxiety involves understanding and nurturing the mind-body connection. Whether through nurturing the Water element, preserving Jing, or enhancing self-confidence through self-defence, Tai Chi offers a comprehensive and empowering approach to alleviating anxiety. Incorporating this practice into a lifestyle change may unlock potential paths toward overcoming anxiety and cultivating inner peace.